The Warm-up and Cool Down: Putting the Science back into Injury Prevention

by Austin Pancner. Published November 14, 2020.

As musicians, we have always been told the importance of warming up before we practice our instruments, but how many of us actually do, and do so effectively? In this article, I will be going over a warm-up/cool-down routine that can be done for any instrumentalist before and after a practice session.

The first question to ask is why?

Playing any instrument can be considered an athletic event. Although musicians aren’t required to be in control of extreme amounts of power and force, such as football players, they are required to be in control of:

Fine motor skills involving repetitive movements

Endurance and stamina

Their response during high stress environments and events, often involving a high amount of adrenaline stemming from the fight or flight response

Despite taking force and power out of the equation, the modern day musician is still at risk of developing tension, pain, or injury - the most common being a repetitive stress injury.

The Science Behind Repetitive Stress Injuries

According to the National Academy of Sports Medicine, repetitive stress injuries are caused by poor posture, lack of daily movement, stress, poor movement patterns, chronic fatigue, and muscles that are repeatedly placed and used in a shortened position (e.g. practicing while a muscle is tight). Repetitive movements can place demands on certain muscle groups, and overtime, cause muscle imbalances that lead to postural imbalances, such as upper crossed syndrome (rounded shoulders) or pronation distortion syndrome (knees caving in and flat feet) (NASM, 2014, 96-104).

Another way to think about repetitive movement patterns is thinking of it like pitching a baseball, long-distance running, or cycling. Over time, these same patterns will place abnormal stress upon the body, resulting in poor posture and dysfunction within the connective tissues of the body. This may not seem like a huge deal to you, but to your body, it is treated as an injury. Your body will respond by initiating a repair process known as the cumulative injury cycle.

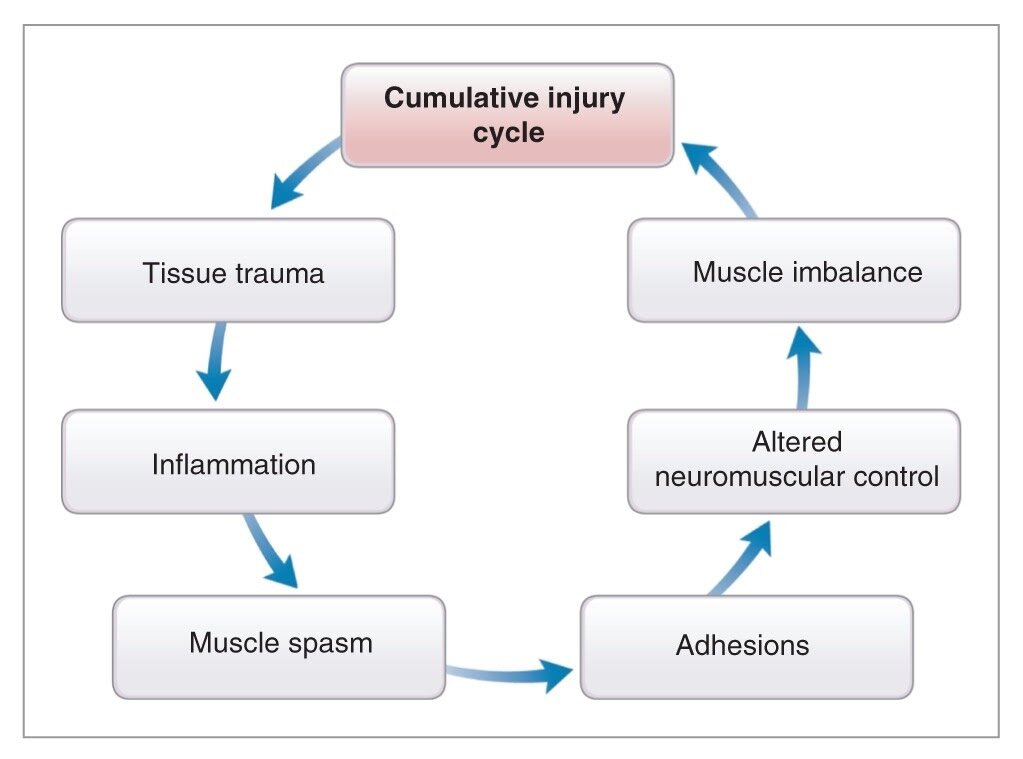

The Cumulative Injury Cycle is the process in which an injury will induce a series of events. As your body repeats faulty movements over time, these patterns cause chronic injury due to pattern overload. Due to the repetition of movement, the soft tissue starts remodeling itself based upon the movement you perform. This tissue trauma leads to inflammation, which causes muscles to spasm and adhesions to form. These adhesions interfere with the natural movement process by limiting range of motion, decreasing elasticity of muscles, and causing altered neuromuscular control. The altered awareness and body control lead to muscle imbalances, causing more compensation and faulty patterns, causing the process to repeat itself over and over again (NASM, 2014, 170-171).

As you can imagine, this is a debilitating cycle and can be extremely hard to break.

One of the most common ways to reduce injury before a practice session is flexibility training. According to Clark and Lucett (2015), the benefits of flexibility training include:

Reduced chance of injury

Prevention or correction of muscle imbalances

Improved posture

Improved joint range of motion

Other benefits, according to the NASM Essentials of Personal Training (NASM, 2014, 172-180), are

Decreased tension of the muscles

Relieved joint stress

Maintenance of the normal functional length of all muscles

Improved neuromuscular efficiency

Improved body function

According the NASM, there are different types of flexibility training, including:

Corrective flexibility consisting of self-myofascial release and static stretching

Active flexibility consisting of self-myofascial release and active-isolated stretching

Functional flexibility consisting of self-myofascial release and dynamic stretching

Self-myofascial release (SMR) is a stretching technique that focuses on the neural system and fascial system in the body. Common tools include a foam roller or a lacrosse ball.

Static stretching is the process of passively taking a muscle to the point of tension and holding it for 30-90 seconds.

Active-isolated stretching involves taking a joint through its entire range of motion, holding for 1-2 seconds, then repeating for 5-10 repetitions.

Dynamic stretching is a process using the body’s momentum and force production to take a joint through the body’s entire range of motion.

For this warm-up/cool-down routine, I chose to focus on active and dynamic stretches in the warm-up, and focus on static and active stretching in the cool-down.

A Couple Things Before you Proceed:

It’s important to note that flexibility training is essential, but not the only habit you will need to prevent the cumulative injury cycle from happening. Regular exercise, deliberate strength training to address your muscle imbalances and weaknesses, and daily health and wellness habits are essential to your long term health and wellness.

When asked to write this article, I was excited, but very nervous, as stretching is used as a “one-size-fits-all” approach in most modern day exercise programs. Stretching has its benefits and should be performed regularly, but with intention and purpose. Everyone’s body is different and as a result, will have different physical demands that will require different exercises at different stages. If you are someone who is experiencing tension, pain, extreme muscle tightness, lack of flexibility, or muscle imbalances, please take caution and address these issues with a professional, before participating in a regular exercise, resistance, or cardiorespiratory training program. Approaching these programs with these symptoms will add additional stresses to the joints and muscles because they have improper mechanics and faulty recruitment patterns.

Guidelines

Always listen to your body, if something hurts, stop!

In each exercise, it is VERY important to brace inward the entire time. Bracing inward is an important concept in human movement and involves flexing your abs inward. Imagine you were walking, and a friend surprised you with a slap to your stomach. Whether you thought about it or not, you braced your stomach because you were expecting an impact! It’s not a lot of effort, but more like a 3/10 on a tension scale!

Be honest with yourself, there will be some exercises where your range of motion will be limited. If that happens, just take note, you are not here to fix anything (this happens away from the practice room)– just to experiment, experience, and discover how your body moves.

If you fall out of a movement, simply settle yourself and try again!

If you experience any pain, please STOP.

10 Minute Warm-up

Hip hinge - 10 repetitions

Standing Cat Cow (or on the ground), 3-5 repetitions

Side Stretch - 5 repetitions each side

Upper back CARs - 3 reps both ways

Shoulder rotations - 5 reps

Shoulder L’s - 5 reps

Shoulder CARs- 3 Reps

Head Mobilization - approx. 30 seconds

Deep Squat w/hold - 30 seconds

Meditation w/ cat stretch (if needed) - 3 minutes

Cool-down, 3-5 minutes

Wrist squeeze and release - 5 reps

Wrist rotations - 5 rotations, both ways

Extended wrist stretch, flexed and extended, 2-3 reps w/5 second hold.

Modified shoulder stretch - 20-30 seconds both sides

Cat cow - 3-5 reps

Thread the needle, 1-2 reps w/ 15 seconds hold or 3-5 reps w/ 5 second hold.

Hip hinge - 5 reps

Deep squat - 30 seconds

Citations

Clark, M.A. and Lucett, S.C. (Ed.) 2015. NASM Essentials of Sports Performance. Flexibility Training for Performance Enhancement (pp. 133-166). Burlington, MA: Jones and Bartlett Learning.

Lucett, S., & Sutton, B. (2014). NASM Essentials of Corrective Exercise training. Burlington, MA: Jones & Barlett Learning.

Sutton, B. G. (2018). NASM Essentials of Personal Fitness Training (6th ed.). Burlington, MA: Jones & Barlett Learning.

Biography

Austin Pancner is the founder and CEO of The Functional Musician, an online coaching company that helps classical musicians perform without pain holistically. During his graduate studies, after switching to bass trombone, he struggled through a three year injury cycle that led him down a path to create a health and wellness system that can help musicians overcome tension, pain, or injury and sustainably support their lifestyle and career path. As a health and wellness professional, he holds several accredited certifications from the National Academy of Sports Medicine, Precision Nutrition, and Functional Movement Systems.

As a trombonist, Austin ran a 40 student low brass studio in Bedford, Indiana and has regularly performed with regional orchestras throughout Indiana. Austin has also found some success in solo competitions. In 2018, he was a finalist at the ATW Bass Trombone Solo Competition and in 2020, he was the runner up in an Indiana regional solo competition involving pianists, strings, and woodwinds. Currently, Austin is finishing up his doctoral studies at Indiana University, with an expected graduation date of Fall 2021.

Website: www.thefunctionalmusician.com

Instagram: the_functional_musician

LinkedIn: The Functional Musician

You can contact Austin Directly at thefunctionalmusician@gmail.com or shoot him a message on Instagram or LinkedIN.